Mirrors

Mirrors were no longer a novelty in the eighteenth century. Improved methods of production led to a greater output of glass and to larger plates. Very large mirrors were still expensive, but small wall and toilet mirrors in simple styles were cheap enough for tradesmen's houses. In larger houses mirrors of all kinds adorned the best rooms, from smaller wall mirrors to pier and chimney glasses, often combined with wall-lights (sconces and girandoles), and their conspicuous position singled them out for highly decorative treatment., especially gilding. For this reason it cannot be said that mahogany played any decisive part in their development. In the Kent period pier glasses, already reaching a height of six or seven feet by the 17305, were given brightly gilded frames and broken pediment tops, and this design affected wall mirrors in general. The pediments sometimes ended in a graceful acanthus leaf, and there was a prominent central motif in the form of a spread eagle, cartouche or shell. The gilding was carried out on softwoods. On the other hand, the simpler kind of Queen Anne mirror with carved flowing curves on crest and apron piece continued to be made. These had mahogany frames, sometimes partly gilt, and incorporated a dominating centre-piece in the prevailing fashion.

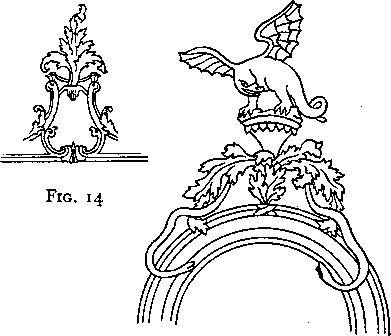

There was a distinct change after the mid-century, when mirrors provided perhaps the best examples of the almost fantastic limits to which the new styles could go. Several designers, including Lock, Copland and Johnson, paid particular attention to applying rococo and Chinese ornament to mirrors, and these trends were made fashionable by Chippendale, who employed the first two to produce designs for the 'Director9. Mirror frames now avoided a symmetrical appearance and were carved and gilded in an intricate pattern of scrolls and foliage in the rococo mode (Fig. 14), and to these were added numerous Chinese designs like exotic birds, pagodas, mandarins and bells, or even Gothic elements. Nowhere else were these styles so intimately united. This vogue did not last long, for Adam, and after him Hepplewhite, designed beautiful and delicately proportioned mirrors, oval or rectangular in shape, surrounded by much simpler scrollwork picked out with paterae, husks and honeysuckle and leading up to a vase or similar classical motif. Adam favoured gilt work, usually on carved pine, and he used the mirror frames to show fluting, the key pattern and Vitruvian scrolls.

Typical of the Sheraton and Regency periods was the circular gilt mirror, one to three feet in diameter. The gilt frame usually had a fillet on the inside edge and a reeded band on the outside; between the two was a pronounced hollow filled with small circular patterns of flowers or plain spheres. Above the frame was foliage, usually the acanthus leaf, supporting an eagle, one of the most popular designs for mirror crests during the whole of this period, or a winged creature

|

|

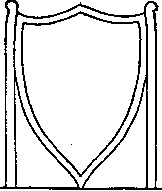

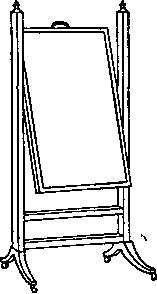

Mahogany played a much more important part in the evolution of the toilet mirror. From early in the eighteenth century many dressing-tables were designed with collapsible mirrors which fitted into the tops of the tables, and the latter usually followed the design of chests of drawers, with a knee recess. But there was a great demand for the separate toilet glasses, the rectangular swing mirrors above minute drawers, made in mahogany. They preserved their simple, attractive shapes and avoided excessive decoration. In the Hepplewhite period the mahogany frames followed the design of the shield-back chair (Fig. 16); later still, about 1800, they became flat rectangles. The tiny chests of drawers were often veneered and had serpentine or bow fronts. Sheraton devoted much skill to incorporating mirrors in dressing-tables. He also popularized cheval glasses, known for some time before. These tall glasses stood between two uprights ending in outward curving feet connected by a stretcher, and had decorative headpieces often painted, inlaid or fretted

|

Philip Burke has a wide range of 18th and 19th century English and continental antique furniture. The different styles of antique furniture that comes in may only last a few days in the workshop before they are sold. If you require a piece of furniture not listed please call and we will do our best to cater for your needs.

|

Philip Burke has been involved in restoration work for a number of years dealing with all aspects of antique furniture restoration and conservation Antique furniture is not always beautiful and pristine--in fact, some of the most valuable pieces show wear and fading. Whether or not to restore antique furniture can be a complex question, but it also depends on the definition of "restore."

|

Based in the heart of Kensington, Philip Burke is in the ideal location for servicing clients from around the London area's. If you require a home visit or just want some advice on your antique furniture please do not hesitate to get in touch.

|